Padraic Colum : Longford Writer and Riot Inciter

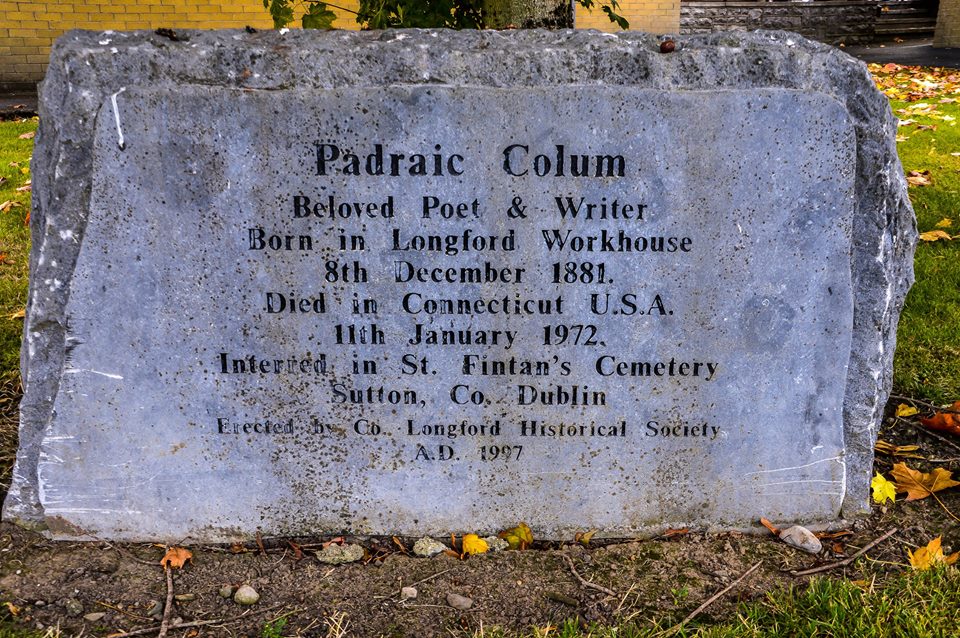

Padraic Colum was one of Longfords most famous modern literary figures. The son of a workhouse master, he grew up in the Longford Workhouse, was the cause of the awakening to the cause of Irish freedom of Constance Gore Booth, and was a noted encourager of James Joyce when he had lost heart in the validity of his work.

He had stayed in a cottage in Ballally in Dublin, and on moving out, the next tenant was Constance Gore Booth, who read copies of the “Peasent” and the magazine “Sinn Fein” which he lad left behind him, which convinced her to become an activist for the cause of Irish freedom, which was to be a major contribution to Irish freedom and feminism in general, and totally by accident. In such a way the muses and the gods of Destiny work and move! She was already an advocate of Home Rule, and her family were noted for feeding the poor on their estates in the preceding decades back to Famine times.

But it was not just Irish literature and the Irish literary conscience that he helped survive and grow into what it is today – after moving to America his reputation spread fast in the right circles, and he was commissioned to write down the Hawaii islands folklore in a format suitable for children, which he published there in no less than three volumes.

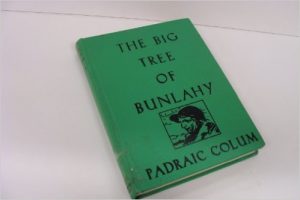

This of course was not his first work for children, being the author of the iconic work “The Big Tree of Bunlahy: Stories of My Own Countryside”, having numerous stories for children published in the Sunday Tribune, and the book “The King of Ireland’s Son” among others, so much so that for many they became the defining genre folk and critics thought of when his name was mentioned.

However for me, and perhaps fittingly seeing my own love of and practice in poetry, its as a poet he is known.

As a child, one of my mothers favourite verses that she read from the Irelands Own was “Old Woman of the Roads” which was in every schoolbook in her youth. This is typical of Colums writing, it was straightfoward, and led the reader to be able to imagine the scene of which he wrote, in this case of a Travelling woman wishing she had the comforts of the settled houses in which she stayed while moving through the land.

While some may say its a naive take on Traveller culture, a gadje (non romany) romanticism of the nomadic lifestyle, they fail to take into account the fact that at that time the “Travelling folk” as they were known comprised of modern Irish Travellers, as well as the now disappeared / integrated Spailpin and other tramps of the road, and they lady of whom he wrote may well have been of the latter of these two as of the former that one thinks of when the read the verse today. In those days the Spailpin were known as itinerant as they lived an itinerant lifestyle, moving annually as tradesmen or teachers, on of the few trades for which they were known. In an effort not to be confused with them is why the Travellers objected to being called itinerant, as they led a totally nomadic existence.

My own favourite verse of his was “The Drover”, the freedom and closeness to nature that the cattle herder had who brought his charges from market to the farm to which they were bought. Like the Spailpin they are now but a romantic memory, the modern industrial cattle lorries of the cattle dealers have little of the character and non of the charm of the weatherbeaten features of the drover who brought tales from parish to parish, county to county, and often slept beneath the stars in all weathers with his charges. A hard life by all accounts, well captured in the straighforward words that are accessable to all readers no matter how little poetry they read or enjoy.

He was widely traveled himself, having lived with his wife Mary in France for a number of years, assisting Joyce morally and in putting together such projects as Finnegans Wake, their close relationship as Irish abroad and as writers chronicled in the book “Our Friend James Joyce” which is full of anecdotal tales of them working together.

As an educator he had lectured in Columbia University, and he and his wife became American citizens in 1945 as did many Longford folk before and since.

He was also one of the lesser known figures of the Irish Literary Revival, having a number of plays produced on the stage in the early part of his career, but his contribution to the drama scene of Ireland was marred itself by drama in the fallout following the riots over “The Playboy of the Western World” which were also incited by Arthur Griffith, on the pretext it made the Irish look bad and was morally questionable. His most famous play today is the anti conscription themed “The Saxon Shilling”

His wife Mary Maguire was a fellow student in UCD, she worked in Scoil Eanna, and together along with David Houston and Thomas MacDonagh they published the “The Irish Review”. Together they went to America in what was meant to be a short few weeks but lasted many years. While there he published collections of childrens poems in local press, which became the book “The King of Irelands Son” on the suggestion of collaboration with and by the Hungarian Willy Pógany.

These are but a small selection of the works of this Longford writer, who published over 60 books, and that is not counting his plays. It is a pleasure I encourage the reader of this article to explore by Googling online that does little justice to the man, his passion for writing and the creations of the written word he left the world all the richer of when he died aged 90 in Connecticut in America. He is buried in Sutton in Dublin, far from his native Longford where he is remembered fondly today.